Mount St. Helens: Part One

*Completed by Brian solo in 2007, Mount St. Helens via the Monitor Ridge Route was his second Bucketlist adventure. It is one of the best day hikes in North America for sure, but be warned: This is NOT something that anyone can just show up and do. It is a long, steep, difficult and potentially dangerous hike, tightly controlled by permits and quota systems.*

**This hike was completed in 2007 and BecauseItzThere apologizes in advance for the quality of the photos which is below our usual standards…Brian was unable to find any digital copies of the pictures and had to settle for mining what Cam Honan calls “shoebox purgatory” for old 3 by 5 glossies.**

It is a name even those who know nothing about mountain will inevitably recognize, known far and wide as a place of infamy.

The reputation is well deserved. In 1980 a cataclysmic explosion ripped the top off of Mount St. Helens, disfiguring it completely and ravaging the landscape for miles around. Despite the fact that there had been ample warnings that the volcano was awakening, at least fifty-seven people were killed by the eruption, by far the most deadly and destructive volcanic even in United States History.

Brian, then in sixth grade, remembers hearing of the eruption, like most on the East coast, on the evening news. He recalls his science class the next morning discussing the even.

He never at any point in his childhood dreamed he would go to visit St. Helens, let alone climb it.

The idea of climbing it first surfaced in the early 2000’s when a friend at work mentioned it. Brian, who had by then been hiking for a few years, initially dismissed the idea as too difficult and risky. (The mountain was continuously active from 2004 to 2008.)

However, the further into it he researched, the more Brian became convinced he could in fact tackle the mountain, assuming it was done during a window when the forces of nature were docile. Successful ascents of Mt. Katahdin and Huntington’s Ravine boosted his confidence, as did a North South traverse of the Grand Canyon in 2003 and a 50 mile section of the AT in 2004.

Climbing Mount St Helens is not easy, even when the mountain is cooperative. What remains of the peak is a basically jagged 8300-foot-tall stump; the landscape, lacerated by the blast and subsequent landslides and ash falls, is raw and rough, having yet to be tamed by the moderating forces of erosion. Though not a technical climb, this is still more than just a day hike. The route (much of it is not strictly speaking a trail) is steep, and the conditions on the exposed peak often adverse. Injuries and deaths, mainly from falls, are common.

When the mountain is uncooperative, climbing is simply impossible. Not wishing a repeat of the 1980 disaster, no climbers are allowed anywhere near St. Helens if it shows signs of erupting.

And while it may seem that all this would serve to dissuade all but the most fatalistic of hikers, the opposite is true. This is a very popular hike – so much so that federal authorities require permits and have placed strict quotas on the number of hikers in peak season. Hikers apply for these permits many months in advance, and in peak season it is not uncommon at all for all the permits in a given day to sell out.

Brian prepared as best he could for this adventure, even to the point of purchasing a pair of goggles to take with him as eye protection in case blowing ash became an issue. (Ski goggles being too bulky, he decided to make due with swim goggles instead.) But living in Texas at the time, there was simply no preparing for the monstrous mountains of the west, let alone this monster of monsters. Prior to this Brian had never set foot in the State of Washington, nor had he attempted a hike of a real volcano.

But this was about to change.

Like most who attempt this hike, Brian applied for and got his hiking permit well in advance. Those who don’t do this risk missing out on the hike; the quota system in season is strictly enforced, and peak weekends can fill up within days of the permits going on sale.

On the way in, Brian had great (and a little close for comfort, to be truthful) glimpse of Rainier right out the window of his plane as it approached Seattle for a landing. This was a bit before high quality cameras were routinely embedded in mobile phones so I have no pictures to show. Trust me it looked cool.

The mountain is almost 100 miles from Seattle; it is actually closer to Portland Oregon, but it isn’t really close to any populated area. The drive in is quite scenic, but we had no views of the mountain at all on the approach, just a low swath of clouds.

Signs of the destruction that resulted from the 1980 eruption were everywhere and easily observed, 27 years after the fact.

We stopped for a day tour at Johnston Ridge Observatory, which is effectively the Volcano’s welcome center. The mountain was, however, not in a welcoming mood. Though the observatory boasts a birds eye view of the shattered eruption crater from a scarily close distance of just four miles (it is well within the 1980 blast zone) there was none of that to be had on this day…the mountain was completely obscured by heavy fog.

Johnston Ridge Observatory is named for USGS geologist David A. Johnston. On the morning of May 18, 1980, Johnston was camped at an observation post just six miles from the volcano. When it erupted, he was the first person to report it to the outside world via 2-way radio. What happened next no one will ever know…his body has never been recovered.

Johnston was well aware of the risks, and in fact had strongly lobbied for the closure of the area, a move which doubtless saved many lives. He chose to be there anyway, doing what was his job and his passion. His life and work are memorialized today by the observatory.

The mountain remained hidden while we visited, but on the winding route down from the Observatory St. Helens threw off its cloudy cloak and materialized quite suddenly from the mist. It was shocking how something that big, that close could hide so completely.

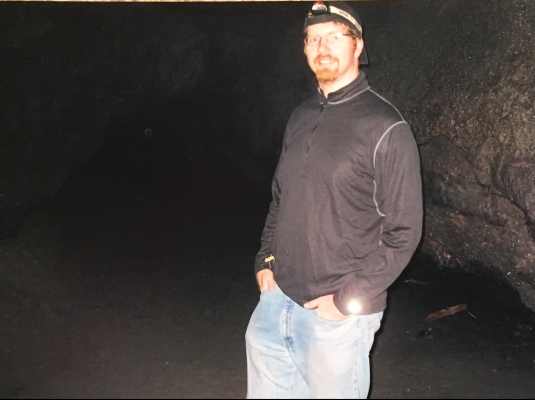

Another side trip in the St. Helens area is Ape Cave, which is an extinct lava tube formed thousands of years ago. There are to my knowledge no actual apes in this cave, apart from the one pictured below. Apparently the cave took its name from the local boy scout troop that helped explore it. I assume the name was in turn taken from the legendary ape that the region is famous for. If you don’t know, the Pacific Northwest is the epicenter of the Sasquatch sighting industry.

At any rate no Sasquatch were sighted on this trip. Brian ain’t much for caves, truth be told. He stuck to the easier lower cave, which is impressive for its height and regularity, looking much like a subway tunnel until you reach the collapsed areas. There is a more difficult to explore upper cave that requires crawling…but as explained, this ape ain’t much for caves and didn’t fancy going there.

But all this monkeying around was just a warmup for the real thing. The next day we would hike Mount St Helens…a mountain that just a quarter century before had lain waste to an entire region.

Next Up: Above the Sea of Clouds