What are the Most Dangerous National Parks for Hikers?

Last time we talked about safety in the National Parks and speculated if accidents in the parks are on the rise. We were unable to find any evidence this is so.

But the parks remain wild and potentially dangerous places. The wildest of them are not places to tread into lightly. Which actually are the most potentially dangerous National Parks?

Outside Magazine Online published a list a few years back of the “Most Deadly National Parks.” As we discussed in our last post, the list is greatly misleading. For starters, there are NO “deadly” US National Parks as the term is popularly understood. The dictionary defines deadly as meaning ‘able to cause death’, so by that definition, every stretch of highway in the United States – and every household tool and appliance – is ‘deadly’.

That’s not exactly the common usage meaning of deadly, which is something more along the lines of, “MORE than likely to cause death if mishandled or handled with violent intent.” The likelihood of perishing in a US National Park is simply too low to make them worthy of the term deadly. It would be like calling fish or chicken ‘deadly’ as opposed to pumpkin pie because of the increased risk of choking.

There is of course danger inherent in wild, remote and rugged landscapes. Falls, mechanical injuries, mishaps that result from getting lost or isolated from rescue, avalanches and -yes- dangerous animals are all potential risks, and you can find all of that and more in the US National Parks, especially the bigger, more remote parks of the West.

Let’s rule out of a few risk factors that don’t really pertain to hikers…We could call these ‘non-exotic’ risk factors. Things that could happen to a person just about anywhere, or at least are not specific to wild areas.

- Automobile accidents. As we have stated elsewhere many times, the most dangerous single aspect of hiking is driving to the trailhead. But auto accidents can happen anywhere and are better classified a risk factor associated with modern life in general.

- “Other Transportation Crashes.” This means airplanes and helicopters. Small aircraft are commonly used as a means of accessing remote areas for both official and commercial purposes. The risks associated with flying small aircraft are much greater than those associated with large commercial airliners.

- Most Drownings. Boating, diving and recreational swimming accidents comprise the majority of drowning incidents, and these don’t really concern the hiker (they do concern the paddler of course, but paddling deaths in the parks turns out to be a very rare event.) Hikers are exposed to the risk of so called ‘dry land’ drownings — crossing fast moving streams or being swept away by flash floods. These however are the minority of drownings.

- Suicides and homicides. Astonishing as it may seem, suicides are one of the leading causes of death in National Parks. This probably says more about how seldom accidental deaths occur in National Parks than anything else. Homicides are very rare in National Parks.

- Pre existing medical conditions. Mostly, these are heart attacks, and mostly these happen to people who are elderly or whose health is poor. This doesn’t fit the profile of the majority of hikers, who are generally in good physical condition.

What’s left? Breaks down into a few distinct categories…

- Falls

- “Environmental Factors” (cold, heat, etc)

- Avalanches

- ‘Dry-Land’ drownings

Avalanches are a very distinct type of event that almost always occurs in very remote areas during winter or early spring; see our risk factors page for more details but suffice it to say that avalanches generally pose little threat to the average hiker. Climbers and extreme skiers need to be aware of the danger, though.

The two biggest ‘real’ risk factors for hikers are mechanical injuries from falls and events that get lumped under the broad definition of ‘environmental factors’, which basically means exposure to the elements. These are the true risk factors associated with large, rugged wild and remote areas…the things hikers, and outdoor recreationists in general, need to watch out for.

Deaths from wildlife, by comparison, are extremely rare.

So now that we have discussed the risks, what are the most dangerous National Parks for hikers?

Once the ‘non-exotic’ deaths are removed, the Grand Canyon leaps to the fore. Long a trap for unwary hikers, an estimated 671 deaths have been recorded in the Grand Canyon going back to its initial exploration in 1886 (this includes pre-National Park times.) Hardly a year goes by when somebody doesn’t fall to their death there, and emergencies resulting from heat and dehydration are almost a daily occurrence at the South Rim. If it were not for the many rescues performed by NPS staff, the fatality total would be much higher.

One might think that the Alaskan National Parks would be exceptionally dangerous places, but the numbers do not bear this out. Denali alone has accounted for a number of fatalities, but the majority of these were suffered by alpine-style mountaineers and rock or ice climbers. It goes without saying that mountaineering is about as inherently dangerous an activity as it gets.

This is not to say that Denali is without its dangers. However, it is hard to reach, has no established trail system, and is in general a formidable place; it’s a safe bet that not too many people set off into the Alaskan backcountry with just a bottle of Evian water and a tourist map.

But it is a safe bet that a lot of unprepared, ill-equipped hikers DO set off into the Yosemeti backcountry, and this might explain why the park records more deaths per visitor than even the Grand Canyon – nearly a third of these being falls. Half Dome alone has killed at least twenty people. Again, one suspects that a great number of inexperienced hikers coupled with a great number of opportunities to do something foolish is the root cause here. There are simply a lot of dramatic places in Yosemeti to take both a great picture and a great fall, sometimes at the same time.

Having visited the area twice and both times been very impressed with the rugged combination of terrain and weather conditions, Brian also expected to see one of the major parks of the Cascades – Mount Rainier or Olympic – in the top ten and was a little surprised when they didn’t show up. Both are among the most visited of the National Parks, and Brian personally witnessed TWO rescues in progress while in this region. All he can say is…whatever the statistics may say, be wary of the Cascades.

In fact, if Brian had to list two parks that impressed him for having potential for things to REALLY go to sh-t, he would say Olympic National Park and Big Bend National Park. Both are remote, rugged, home to extreme conditions and filled with things that could kill you.

This whole project began after Brian read an account about a man falling and injuring himself in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. That park is not considered one of the more dangerous, despite the active volcanism. Hawaiian volcanoes tend to be rather low key volcanoes. Living in paradise even seems to rub off on them.

On that note, it has been speculated that the rise of Selfie Culture has led to an increase in the number of ‘this didn’t need to happen’ type accidents like the one that recently happened at Kilauea. But we are unable to find any evidence of a sharp uptick in the number of falls recently that isn’t readily explained by rising number of visitors.

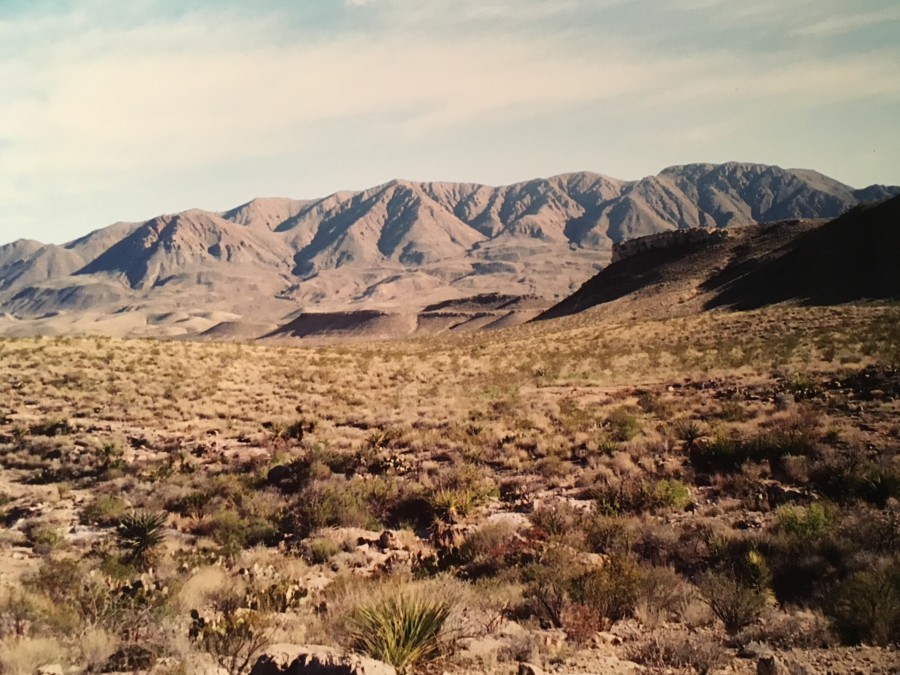

Our conclusion is that the most inherently dangerous National Parks for hikers are almost certainly the larger parks of the west – especially those of the Redrock Southwest (like Grand Canyon) followed by those of the Rockies, Sierra Nevada and Cascade Ranges, followed maybe by the Big Bend of Texas, with Alaska in there somewhere.

But really it depends far more WHAT you are doing than where you are doing it. Off trail hiking is always more dangerous than on-trail, hiking on rough terrain riskier than on flat, etc. And certain places, like Half Dome or Yellowstone’s thermal springs or any cliff edge, are simply flat out dangerous and should be treated with great respect.

What should the hiker take away from this? In our opinion, it is that there is no severe risk posed in visiting any US National Park. The only real risks are basically those involved in the activities one is doing, be it driving or swimming or hiking. There is absolutely no reason why a visit to any US National Park can’t be a safe and rewarding experience.