The Grand Canyon North-South Traverse

**Completed in 2003, the North-South Traverse of Grand Canyon is the first true Bucketlist hike that Brian ever did. He would recommend this hike to virtually any able-bodied hiker as a once in lifetime experience, if that hiker is well prepared for the canyon’s unique conditions.**

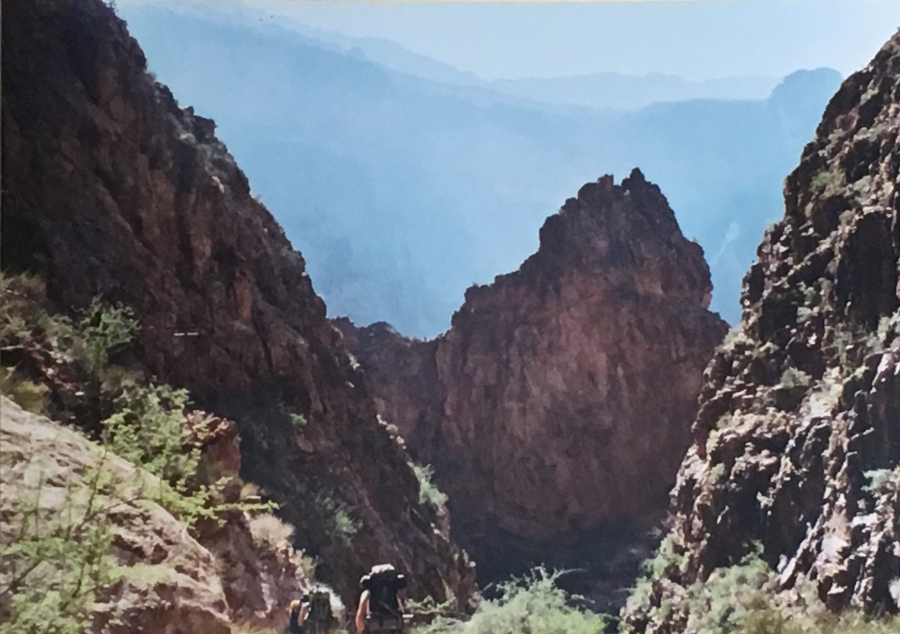

***Note that the editors apologize in advance for the quality of some of the images on this site which are ‘legacy’ pre-digital photographic prints rescued from what master hiker Cam Honan refers to as “shoebox purgatory.”

Millions of people flock to the Grand Canyon from all over the world to experience its immense, breathtaking views. For most, experiencing the canyon will mean visiting Grand Canyon village the South Rim and stand, often elbow to elbow with throngs of fellow onlookers.

Fabulous views are of course what makes the Grand Canyon famous. But there is far more too the canyon than just the views to be had standing at the edge of blacktop, from railed-in walkways at the rim. The Canyon is immense; ninety-five percent of it is unpeopled wilderness. Silence; the strange and wonderfully twisted country of the wild canyon bottoms, filled with cottonwoods and home to puma. The beauty and tranquility of the layers of rock, set down over the ages and meticulously measured out in sandstone. A vast wilderness that even to this day can barely be said to have been explored.

Few visitors will every experience this side — the inside — of the Grand Canyon. Most are content merely to stand at the edge, and look.

Brian is not one of those people. Almost immediately after his visit in 2001, he began to plot a return visit to the Canyon with the specific goal of seeing the aspects of it he had missed the first time. To truly understand and experience such a vast landscape requires more than just standing at the edge and looking. It is necessary to get out of the car, go beyond the guardrails, leave the crowds behind…and walk away.

To be sure, this is not a thing done lightly. The Grand Canyon has long been a trap for the foolish and unwary. In 2017, Grand Canyon Search and Rescue (SAR) teams responded to 290 emergencies inside the canyon, and many of these were hikers who underestimated the difficulty of hiking over the rim.

In fact, many of the rescues involved physically fit young men who had presumed themselves equal to the task of hiking down to the Colorado River and back again in s single day. They proved instead the enormity of the undertaking, particularly when attempted in the blazing Sonoran summer. The Bright Angel Trail, considered the easiest way into the canyon, is a 16-mile round trip with a severe uphill on the return leg. Even for very fit and well-prepared hikers, this an enormous ask for a single day’s hike.

Brian, at this point a modestly experienced Appalachian hiker, was aware of both the dangers and his own limitations. He’s been on hikes in the white mountains where he’d overtaxed himself, underestimated the conditions, even run himself out of water. He was under no illusions that the same poor preparation and faulty execution in the desert would prove disastrous.

Compounding the challenge was the fact that Brian had relocated from Boston to Dallas, Texas in 2003. There’s scarce few mountains in the eastern part of that-there great state of Texas; in fact, it’s four or five hours drive from Dallas to anything that remotely resembles a dang ole’ hill. This did not make the challenge of training for a hike — one of some 23 plus miles, that starts with a 5730 foot descent and finishes with a 4770 foot climb — any easier.

Brian was also seriously concerned about what impact the descent from the Rim with a full pack might have on his ‘trick knee’ which has been problematic throughout his hiking career. He thoroughly researched the trails involved; his exploratory visit to the Canyon, which included a day at the North Rim, greatly helped in his endeavors. In the end he decided that he could in fact complete the full traverse.

To prepare, Brian got himself into perhaps the best shape of his life, not only working out four times a week but engaging in the most rigorous hikes he could. At one point he did an exhausting 14 mile out and back on Grapevine Lake’s North Shore Trail, which is probably the best trail in the entire DFW area. One of the most rigorous things about it is dodging the many mountain bikers that share this surprisingly rugged trail.

Trick knee or no, the decision to do the hike from North to South is easily made. The North rim is more than 1000 feet higher than the South; not only does one have to factor in the extra climbing needed to ascend, but the fact that the high altitude (8000 feet) of the North Rim itself makes uphill hiking more difficult. Coming down that high north escarpment is entirely more sensible than going up.

Having decided on the route, it became a question of logistics. Either way you do it, the hike requires a very long vehicle shuttle. Though the rims of the canyon are but ten miles apart (you can see the roof of the Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim quite plainly from the El Tovar Lodge on the South) due to the fact that there are NO vehicle bridges over the Colorado River between Marble Canyon and the Hoover Dam, they might as well be in different states,

All access between the rims that does not go by foot or by aircraft goes via Navajo Bridge at Lee’s Ferry…here, one enters the remote corner of the Southwest known as the Arizona Strip, a wild and mostly unpopulated area the size of Massachusetts so cut off from the rest of the state that it is almost an extension of Utah, if not a separate entity unto itself. The very scenic one-way trip of over 200 miles requires more than four hours. It is one of the most scenic drives in the US and we very much encourage you to drive it – but it makes for difficult logistics when doing a cross canyon hike.

Brian had driven all the way to the Canyon from Boston on his first visit but had no intention of repeating this venture. This time he would fly. Since the hike would start on the North Rim, it made sense to fly into Las Vegas, rather than Phoenix, Vegas being almost two hours closer to the North Rim.

For the equipment Brian decided to go as light and minimalist as possible. He used his old White Mountains era Lowe Alpine backpack, stripped down as much as possible for light weight (he even went so far to remove the internal supports and cut off the excess lengths of strap.) He did not figure on needing much insulation, and so brought his light Sierra Designs sleeping bag that served him for a decade and a half, plus a few light layers and rain gear just in case.

He left the tent at home, and for shelter selected a very lightweight (1.25 pounds, almost unheard of at the time) North Face one-person bivy sack. He banked on the fact that very little actual shelter would be needed. His prior experiences in the canyon at around the same time of year thoroughly convinced him that if he were to die of anything, it would not be hypothermia.

By this point Brian had already converted over to a bag-and-hose ‘platypus’ style hydration system, so no change in strategy was necessary.

The hike was timed precisely at the shoulder season of the canyon, at the very end of September…In October, the rest houses on the South Rim of the canyon start to shut down for the season, an event which would have major ramifications for a hiker as the water pumps likewise shut down.

On the advice of the great southwestern authority ZZ Top Brian went out and bought himself a pair of cheap sunglasses.

These ‘El Cheapos’ had the unfortunate effect of making everything look rather yellowish but served their purpose.

As a final gesture, Brian debuted for the first time in recorded history what would become the cornerstone item of his ‘tropical kit’ — the celebrated (and much maligned) Gilligan Hat. The theory being that any headgear that could protect the brain of an idiot from the tropical sun must surely have a similar effect in the desert.

The Gilligan Hat continues in use to this day, much to the frustration and embarrassment of Sylvia (who very politically states that she “doesn’t care for this hat.”)

Most people take three days to hike this itinerary. My original plan was to stretch this out to four; however, time and logistical pressures caused the group I was going with to opt very reasonably for the three day option.

The plan was…

(Hike Day -1, camp at North Rim)

Hike Day 1: 6.8 Miles

North Kaibab Trail to Cottonwood Campground

Hike Day 2: 7.2 Miles

Cottonwood Campground to Bright Angel Campground (near Phantom Ranch)

Hike Day 3: 9.5 Miles

Bright Angel Campground to Bright Angel Trailhead

Total Miles: 23.5

(Hike Day +1, Return to the North Rim via shuttle.)

At the time, this would mark the longest single hike Brian had ever attempted. Previously his record was a brutal 2-day death march through the Bonds in the White Mountains which probably had not totaled much over 20 miles (though it had felt like 200.) This was going to be the most significant hike Brian had ever attempted – and the first of a serious kind that he had attempted in desert conditions, hitherto foreign to him.

Could he do this, or was it simply too much? Thoughts of this kind were foremost in his head as Brian set out, ticket in hand, for DFW airport for a flight to Vegas. Gambling of the ordinary kind was not what he was after…his stakes were set higher.

NEXT UP: Bright Angel