Mount St. Helens via the Monitor Ridge Route: Part Two

Almost nothing about the hike up Mount St, Helens is easy. Even reaching the trailhead involved some serious driving. The Monitor Ridge hike leaves Climbers Bivouac, which is located on forest service roads some ten miles outside of the tiny town of Cougar. But it’s a good hour from the accommodations along the I-5 corridor. Thus, it behooves one to get a good early start for the summit.

Brian alas was insufficiently behooved on this day, getting a late start due to oversleeping which he blamed on an uncooperative alarm clock. The drive to the trail head was as gray and dismal as the day before, when we had found the mountain completely obscured by fog and clouds until almost the end of our visit. We had to hope that the sun would win the fight eventually, but early on, the smart money seemed to be on the clouds.

As companions on this hike Brian joined his good friends John and Val Murphy from New England, who had hiked with him on the Rae Lakes Loop and the Grand Canyon.

The first two miles of the trail are on a regular trail, the Ptarmigin Trail. This trail, maintained by the excellent Washington Trail Association, is somewhat steep, but generally well graded with solid footing. This section is also completely in the trees. We encountered no rain on the way up, but the fog was thick enough to cut with a knife.

At a little over two miles, and at 4800 feet elevation, the trail breaks out from the trees and into a completely different world. Here, large banks of debris mark where lahars – pyroclastic mudslides – rolled down off the volcano during the 1980 eruption. The trees and vegetation abruptly vanishes, and one emerges into a plain of ash. Straight ahead the volcano rises, but we couldn’t see it.

Here, there is a junction with the Loowit Trail, which makes a scenic and challenging loop around the volcano. (The authoritative WTA website describes this trail as a sort of evil twin of Rainier’s Wonderland Trail…being “impossible to predict if the circumnavigation is “doable” at any given time for any hiker.”)

Here, we decided to rest, have a snack and layer up before the real challenge begins. While we did so, we noticed a large party, perhaps a dozen men, carrying a gurney down the mountainside. In the ten minutes or so that we sat about resting, the party hardly moved twenty yards over the rough terrain.

This turned out to be a SAR rescue squad. A man had fallen on the mountain the previous day and ended up spending the night up there somewhere on the side of the volcano. Though he was not seriously injured, he had been unable to come down under his own power; this was the result. A SAR team was painstakingly descending the mountain, at great risk to themselves, to transport the injured man back to Climbers Bivouac where county EMS would take him on to the hospital.

Watching the team work was both excruciating and sobering. It was a reminder that it you messed up here, there was no easy way out, no quick way off the mountain. The lesson: you definitely do NOT want to mess up here.

At the junction with the Loowit Trail the Ptarmigan Trail ends and the true Monitor Ridge Hiking Route begins. You need to have a permit to go beyond here. There is no specific trail along this route; it is marked in its lower extremes by poles set at intervals. Higher up there are no markings at all, though the way upward is obvious, at least in good weather.

The route is MUCH steeper than the Ptarmigan Trail; in fact, it may be the steepest hike Brian has ever attempted over a sustained distance, rising some 3500 feet in less than three miles…well over a thousand feet per mile, making it comparable with such monsters of Brian’s White Mountains days such as Huntington Ravin, the Great Gulf and the North Slide of the Tripyramids.

It is also very exposed — nothing of note grows here apart from rock and ice. Mercifully we could see only limited views of the top along this section, as we were still clouded in. Every time a swath of the upper mountainside did appear, it was a daunting sight, seeming impossibly far away up a slope that looked quite vertical. This is not a place for the faint of heart.

The first two miles or so of the route ascend through a boulder field and this is the most treacherous section. As astonishing as it seems, all the rock around you is brand new by geological standards…the landscape having been fully and violently recreated just decades earlier. The volcanic rocks are jagged sharp pieces of grayish pumice…they don’t look razor sharp until they flay your hands open or rip you clothes to shreds. Many accounts of the hike recommend bringing heavy gloves of the type used for yard work; Brian, alas, had failed to equip himself with these, and was cut up a bit, though not seriously.

Another danger through this boulder field is rockfall…there are tons of loose rock lying around everywhere, and on the steep slopes it is perilously easy to dislodge one and send it hurtling down the slopes toward hapless hikers below. At least once Brian saw this exact scenario happen, forcing him to call out a warning on behalf of another stunned hiker. The person below covered up and escaped injury as a cantaloupe sized rock went crashing past.

If you can make it past the boulder fields the most dangerous section (barring the very top) is over, but the work has only begun. The last mile or slow is an arduous slog up a steep slope of powdery ash. Think of walking on an inclined sand beach…the result is best described as one step forward and two steps back. It takes a LOT of exertion to get through this portion, but at least it isn’t that dangerous…if you fall, it’s like face planting on talcum powder.

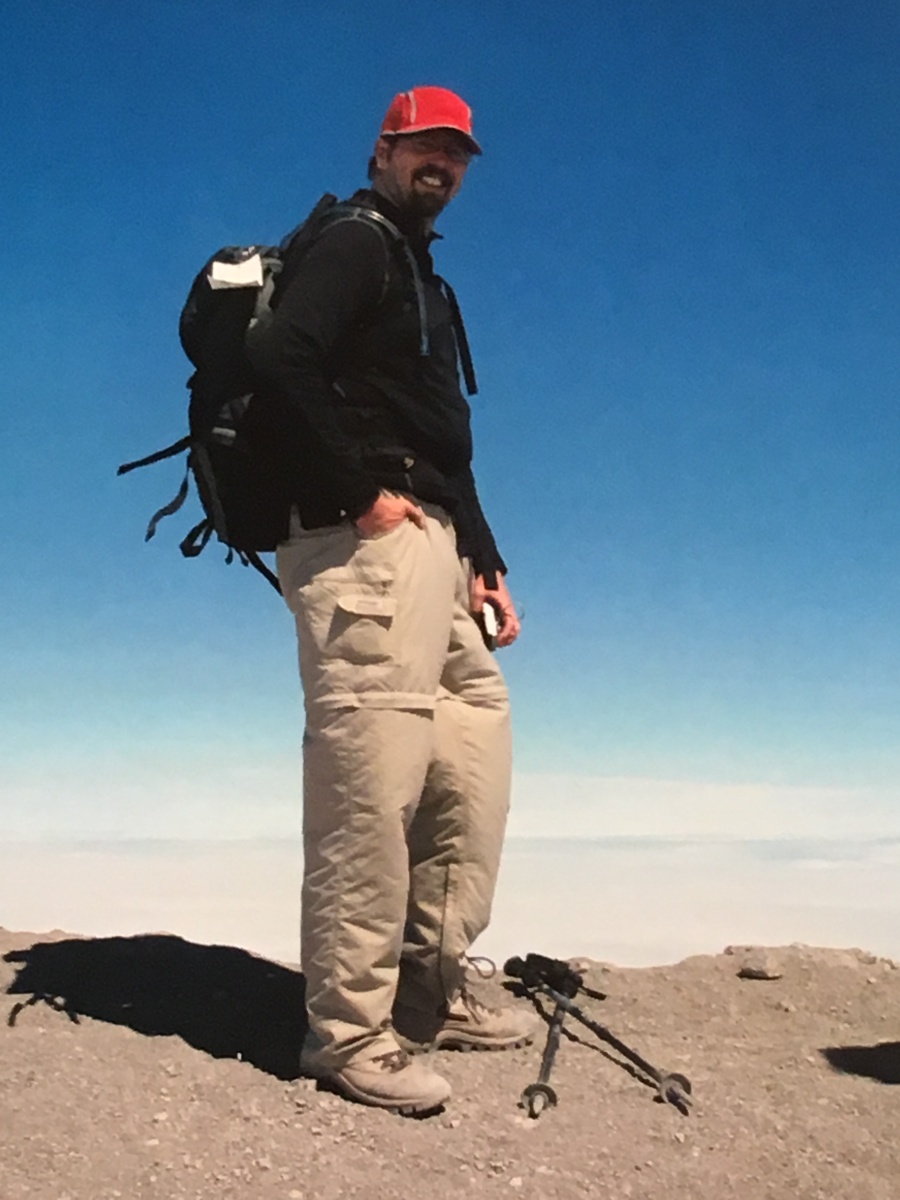

Somewhere around the transition between the boulder field and the ash fields, we broke out of the clouds and into that bright, cobalt blue sunlight that seems native to the Pacific Northwest. Where once the views had been obscure and cottony, now they were clear and unhindered. The uneven mountaintop, still wreathed in patches of late season snow, was completely in view now. Closer, but still very far away.

To our left rose the imposing cone of Mount Adams, the second highest peak in the Cascade Range at 12,281 feet. It seems a stone’s throw bu in fact, it is miles away. Mount St. Helens had once resembled this peak before underworld forces had burst the top clean off. Behind us, at a distance of some 70 miles, rose the even more perfectly conical form of Mt. Hood. These peaks had become islands towering above a sea of cloud. We had broken into a new universe, a skylit upper plain of existence inhabited only by these few high and snow-capped peaks.

We climbed, unable to see the terra firma from which we had come, and the alien perspectives of the skewed landscape started to play tricks on Brian’s brain. There was no other frame of reference in this blue and gray world apart from the distant peaks, and these were too removed to be much of a visual anchor. Brian’s mind kept trying to tilt the horizon sideways to align it with the sloping ground…the result was visual confusion and disorientation. Brian felt himself getting mildly queasy and set himself to merely slogging forward.

And that last bit is a very hard slog, but then…the end is in sight. We crested the lip of the rim, and ahead of us rose distant Rainier, filling the sky, amazing big. There, before us, was the crater. And what a crater it is.

To stand on this edge of this massive, gaping wound in the earth…at the spot where over a thousand feet of mountain blew clear away…well, it’s something that can’t easily be described. The view is like nothing Brian has even seen.

You could look down into the misty-shrouded crater and see, deep within its craggy walls, the very mouth of the volcano. There, an ominous dome of rock bulged copiously. It seemed to pulse with heat and life. This was the 2004 lava dome, which at the time was still growing; the older one dating from the 1990’s stood off to the side beside it, dormant now.

Mount St. Helens was in fact erupting when we climbed it…the period between 2004 to 2008 is considered to be one continuous eruption by geologists. But it was erupting in a very passive way, simply adding to the bulging dome, biding its time. There was little real risk of being there.

As we stood there under the clear blue sky, looking down and through clouds into this hellish landscape, we could hear, feel and smell the volcano. At times we listened to rock falls from within the crater, evidence that the volcano was continuing to belch forth more new landscape. The mist we were seeing was at least in part escaped gasses from within the volcano, and if one descended into that deadly cauldron, eventually the air would become poisonous enough to kill.

It was ominous stand there. Some people go on to follow the ridge to the left, ascended to the highest point which is the mountains new true summit, but most don’t bother. Most come to get this view. Having seen it, and tarried for a short while, most don’t linger longer. It seems enough to tempt fate simply by coming here. No need to tempt it further.

We looked out and below, there was monitor ridge observatory, very far below. We had a better view of it now than we’d had of this spot from it yesterday. Far away behind Rainier were the Olympic Peaks, and east of them was a jagged line that was the North Cascades. Apart from this, all we could see was a carpet of white cloud.

After staying as long as we dared, we retraced our steps down the ash fields. The first part is more of a controlled slide than a walk and is not difficult as long as you don’t do anything stupid. But the descent becomes MUCH tougher in the boulder fields, where one is continually trying to find the route of least resistance between razor sharp rocks, some of which are loose.

To make matters worse, once we re-entered the clouds, we found that it was drizzling. Everything was now slippery, including our ash-layered shoes and clothes. The descent of Monitor Ridge – especially this part of it – was the hardest of Brian’s hiking career to that point and remained the hardest until finally being eclipsed by the brutal descent into Chamonix at the end of the Tour du Mount Blanc a decade later.

Once back down to tree line it still wasn’t over. Still, the two miles of the Ptarmigan Trail, itself steep and now quite muddy, lay before us. We soldiered down, wet and dispirited now. We were however treated to a serendipitous sight though…a crack of a branch in the woods alerted us to movement in the trees, and we watched a mother and calf elk spring off into the woods.

We arrived back at climbers Bivuoac tired, waterlogged, sapped of strength and spirit. The hike had taken everything out of us, and now Brian was on the brink of collapse. But it was still an hours drive back to our accommodations, and so we poured the ask from our hiking boots and set off.

Brian was basically glad to be alive at this point…but only later, after the exhaustion had past and he could reflect on what had transpired, did it dawn on him.

He had done it! He had done the life changing hike to the spot where Mount St. Helens had blown to Kingdome come! He had hiked above the sea of clouds!

The second of his Bucketlist Hikes was officially complete.