Second tier essentials are NOT necessarily less important than the first tier. Simply put, second tier essentials are those whose failure does not pose a serious make-or-break dilemma for the hiker. Loss, malfunction or damage to second tier equipment is more readily recovered from. If a hydration system fails, for example, you can just substitute a bottle of water. If your backpack or pants rip, well, it’s annoying. But if your shoes fail, or your tent rips, this could be a serious situation.

Note that losing all your water could be a VERY serious situation, more on that elsewhere.

The second-tier essentials are Threads (clothes), Hydration System and Backpack.

Threads

Some people think clothes make the hiker. Others say the hiker makes the clothes.

Whatever the case, it is essential that you dress like a serious hiker if you intend to be one. The pluses of doing so:

- You will look you know what you are doing

- You will be comfortable

- You will be prepared for the conditions afield

The disadvantages of not doing so:

- You will look like a tourist (at best)

- You will be uncomfortable

- You may die of exposure

The last is, of course, worst case, but it happens all too often. A person in jeans and a T-shirt hiking above tree-line is a recipe for disaster if the weather turns bad. Hypothermia tends not to make one look cool regardless of how much one paid for the outfit.

We divide clothes into two categories. The layering system (essential) and the comfort system, aka layer zero.

The comfort system (Layer Zero)

If you go hiking in the mountains in summer, there are many potential weather conditions you could face, and you need to be at least adequately prepared to face each one of them. But the MOST likely condition you will face is heat and humidity. It may not be hot enough to kill you, but if you aren’t prepared for heat, you are likely to be uncomfortable. This is not a desirable situation

The comfort system is:

- The clothing that is best suited for the conditions you are MOST likely to face while hiking

- The lightest possible gear you can get based on #1

- Not necessarily part of your layering system

In summer, for example, you probably want to start out hiking in shorts and a tank top or t-shirt of some very lightweight fabric. The insulating ability of these garments is effectively zero, so they aren’t even considered as part of the layering system (hence they are layer zero…they do zero to keep you warm.)

Layering System

The layering system is the clothing that you bring with you to prevent hypothermia, IE freezing to death. Unlike the comfort system, this layer is VERY IMPORTANT and it is critical to chose the right materials. If it fails, you won’t just be uncomfortable, you might be in serious trouble.

Layer 1: Inner layer. Clothing that sits close to your skin. Underwear and long johns.

Layer 2. Various middle layers that exist between the inner and top layer.

Layer 3. Top layer: This is the layer that has the best insulation and will be deployed in the coldest conditions. Note that it is not necessarily the outermost layer. That is…

Layer 4: Shell layer. This is the wind/rain hardened outer layer that is deployed in inclement weather. It should be waterproof.

Note that it is NOT necessary or even advisable to deploy all these layers at once. The idea here is to mix and match as the conditions require. In very cold conditions, for example, you would want to deploy the first three layers at least. But if it is not too cold but raining hard, you might want to deploy just layers 1 and 4.

Central to the idea of any layering system is the concept that as you warm up, you shed layers, and as you cool down, you add them. If you do not do this your layers will actually work against you. In cold and windy conditions, hypothermia sets in when the body can’t generate heat quickly enough to replace what it is losing. Wet skin loses heat much faster than dry. Therefore, if you overheat, and start to sweat, you are setting yourself up for a situation where you are at risk of hypothermia.

What generally happens is this…well equipped hiker sets out in good weather. It starts to cool down, and so hiker puts on a sweater. The hiker keeps hiking, warms up and starts to sweat. But humans being lazy, hiker does not take off the sweaty layer, thinking its no big deal. Then the hiker stops to rest, and after sitting for 15 minutes begins to shiver uncontrollably. Hypothermia, and perhaps death, is just around the corner.

To prevent hypothermia, and its alter ego heatstroke, a layering system is necessary, but so is the wise use of the layering system. Choose your comfort layer based on whatever makes you feel comfortable, but chose your layering system with the utmost care.

Notes on threads:

- You may have heard the phrase cotton kills, and it is true that cotton is a VERY poor choice for a layering system because it loses all insulating ability when wet (it’s actually worse to wear soaked cotton clothes than to go naked.) However, it is a reasonable choice for the comfort layer, because it is cool and comfortable.

- With the above said, we do NOT recommend clothing that is more than, say, one-third cotton for ANY circumstances in the outdoors. Cotton is a sponge for water and slow to dry out.

- There is NO standard layering list, because there is no uniform set of conditions. Clothes should be chosen based on the circumstances. It is obviously not necessary to bring shorts on a winter expedition in Alaska, and it is obviously not necessary to bring a wool parka to the Amazon Basin.

- Clothes that are lightweight, breathable and quick-drying are preferable, but they will also be more expensive

- Don’t get drawn into outdoor gimmicks like sweat wicking this and ultr-light UV blocking that. Just buy a bunch of polyester pullovers, for gosh sakes.

- We recommend convertible pants – pants that convert to shorts by means of zippers.

- A hat and gloves should be part of your layering system.

- On a winter expedition, be sure your hat covers the ears and you have VERY warm gloves for your hands. You might want to invest in a layering system for the hands.

- Cold hands alone won’t kill you, but they will make almost any task difficult or impossible, and that MIGHT kill you.

- The time to layer is when you stop, the time to delayer is when you hike. Resist the temptation to start the hike warm and have to de-layer in ten minutes. You should be a bit chilled (repeat, a BIT) when your hike starts.

- Don’t forget extra socks, Brian carries one extra pair on ANY hike and at least 2 extra pairs for an overnighter.

- Almost any jacket that will stop rain will also stop wind, therefore your rain layer can and should double as a wind breaker

- A poncho is great for looking colorful while herding llamas or alpacas. For stopping rain, it is inadequate. Invest in a good rain suit (pants and jacket.)

- Be aware that in fabric terms, ‘water resistant’ means it will get wet slower and ‘water proof’ means it will get wet slower still. There is NO fabric that stays 100% dry in all conditions.

- NO clothing or temporary shelter will keep you 100% dry in very heavy or prolonged rain; doesn’t matter what you wear, you are going to get wet eventually if it rains hard enough and long enough.

- Most breathable waterproof fabrics are very good at repelling moisture right out of the factory, but degrade over time.

- Waterproof, breathable fabrics must be kept clean and maintained or they lose effectiveness even faster.

- You sweating inside a stuffy rain suit might make you as wet as the rain outside will, though you will be warmer.

- I always carry a full set of long underwear on all long-distance expeditions, if nothing else they can function as a pair of dry pajamas.

- It is a good idea to take a rain layer for any walk of over a mile even in populated areas

- You never get a chance to make a second impression in the woods, so DAZZLE, and wearing white in the woods after Labor Day just ISN’T done.

- Last note: Tolerance to heat, cold, wet etc varies greatly, person to person. It is very obvious that human beings lived in North America for millennia prior to the existence of lightweight breathable clothing. It is also equally obvious that most of us can’t do or endure what the Native Americans did and endured. Our advice here is meant for beginner and intermediate hikers; not for Ted Nugent. If you have been doing what you are doing for years in buckskins, a loincloth or a basic Elmer Fudd getup, it’s obvious you are going to keep on doing it and probably be just fine. We recommend you take the layering practices described here seriously as you start to venture into the outdoors, and wait until you have experience before charting your own path.

The Hydration System

The ‘walkie-drinkie.’ A hydration system is your means of carrying and ingesting water. This is an important piece of gear…apart from your shoes, you will use your hydration system more times a day than any other. Keep in mind the lesson of the camel. The camel does not walk as far in the desert because it needs no water. It walks because it can STORE the water it needs.

In general, every hydration system should be convenient, reliable and effective. This means:

- It is easy to use

- It encourages you to drink regularly

- It is not prone to sudden and frequent breakdowns

- It doesn’t take unusual effort to draw water via a hose, etc.

- It can provide you with water at any time without a substantial delay (ideally, without breaking stride at all.)

How much water you need to carry depends on many things. Generally speaking, for an average day hike two liters is recommended. Note that this is almost five pounds of weight in your pack. The weight of water is not inconsiderable, and is in fact one of the major limitations of long distance hikes. It’s very difficult for the average person to carry more than a two-day supply of water in addition to all the other gear required.

Be aware that if you camp in a place without water, you will have to bring all you need for cooking, cleaning, washing etc as well as drinking.

Our advice is treat all natural water sources by filtering, chemically purifying or boiling. There is no way to know by looking at water whether it is safe or not.

There are many ways of storing water. Make sure your system is functional. Walking around holding a plastic bottle of water, for example, is NOT a functional hydration system. Neither is a bottle of water zipped up in your backpack. This will discourage you from drinking.

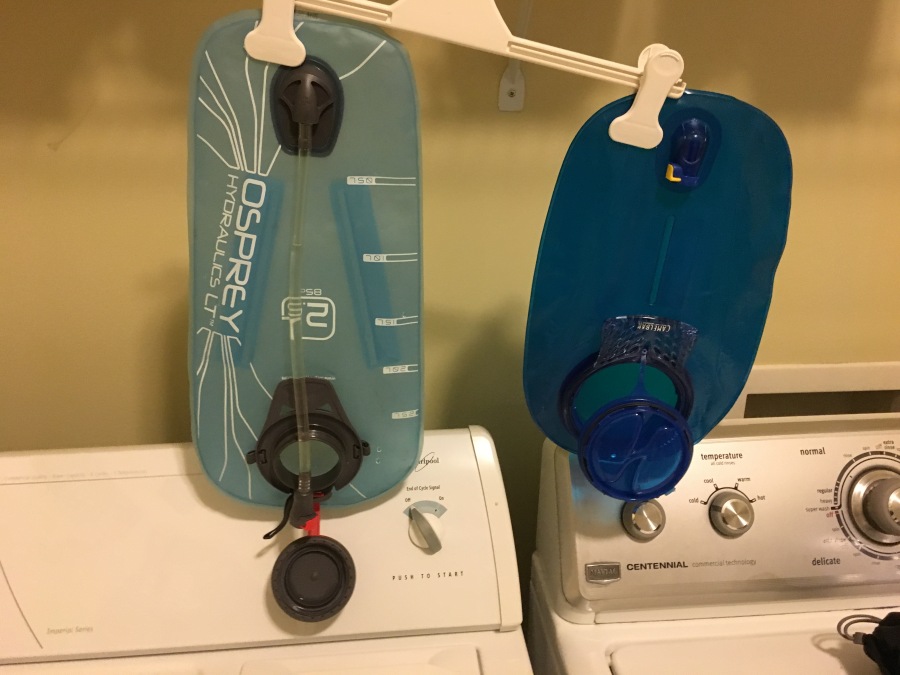

Most hikers these days (including me) use some sort of bag and hose operated hydration system like those developed by the US military, and then popularized by cyclists in the 1990’s. Platypus is the most noted maker of such systems, but there are many in use today. Many of these models are a bit fancier than need be, and in some cases lack reliability and effectiveness. Brian’s personal observations of hydration systems are:

- The more you pay for them, the more likely they are to rupture

- Most of the cheap plastic IV bag types are surprisingly durable and reliable

- Brian has never had a low-end bag fail. He has had MANY high-end ones fail.

- One of the biggest drawbacks of the cheaper bags is they have little tiny openings, making them more difficult to fill.

- The newer ones have bigger openings, but very often the screw-type lids thread very poorly and either don’t close right or leak.

- Some hoses draw better than others, and the most complex types are usually the poorest

- Mice and other animals love to chew through the hoses

- A single small hole or lost rubber widget can render the whole system inoperable

- If you take a bag and hose system on a multiday trip, we recommend the following: An extra bag, spare hose and a cap or stopper for the spare bag

- For hikes in arid areas where water is SUPER important, a hardened bottle is a good idea

Note that some people don’t like the hose/bag systems because you can’t easily monitor use. I don’t think is a significant issue…if necessary split your water into two bags, and when you drink the first you have a good calculation as to how long the rest will last.

Our advice for the novice hiker is to take an old-fashioned hip-mounted canteen on the first few hikes, just to understand the importance and convenience of having a real hydration system. When you finally make the leap to the hose-operated systems, do NOT feel as if you must spend a lot of money, a very inexpensive system is most times the most functional. Instead of spending more on a single component, my advice is to spend your money buying a bunch of cheaper ones for redundancy.

Backpack

This is your hotel on two feet. It has no direct role in helping you to hike or keeping you warm at night or keeping you alive; but without it, you would be unable to carry the things that do: food, water, shelter, sleeping bag etc. The backpack is thus an indirectly vital piece of gear.

It is also, apart from maybe shoes, the piece of gear you will spend the most time complaining about. Therefore, some thought should go into the purchase.

There are no particular rules that we have for selecting backpacks, as most modern ones are so vastly improved over the massive, unwieldy, apartment building style numbers of 30 years past that any way you chose, you probably won’t go that wrong. The main rules are that it needs to be durable and your stuff has to fit inside; if both are true, then it will do the job.

We would make the following recommendations:

- Select a lightweight pack if you can.

- As with most other outdoor thingees, ‘lightweight=expensive’

- Weight is important…But don’t settle for a pack that is so lacking support that it doesn’t sit right on your back. The idea is to have SOME degree of a rigid frame to support the weight so that your skeleton does not have to.

- Don’t get talked into buying special space age back ventilating whiz bangs. The purpose of the pack is to carry a bunch of gear, not fly you to the moon.

- The main compartment of the pack should be roomy enough to carry your standard gear set plus a little extra.

- A pack should feel comfortable under a good amount of weight. Try it on in the store with sand bags or some other sort of weight. When you bring it home, walk around with REAL gear in it for a few days. If not satisfied, do NOT hesitate to bring it back.

- We prefer to have a few extra pockets, but not too many pockets. It’s helpful to know exactly where you put something and having 18 possible pockets to search through doesn’t make that easier.

- Eliminate or minimize the unnecessary straps, snaps, zippers, buckles, etc. It might look cool, but those widgets will end up catching on branches.

- A couple of open pouches on the outside for quickly stowing gear is nice.

- Most packs now have a little pouch inside for a hydration system, plus holes to let the hoses through.

- Resist the temptation to spend oodles of money on a super lightweight pack. The weight savings is often not that great, and many ultra-light products are not very robust.

- Do not buy ANY pack without trying it on first.

- Remember that the weight of a pack should rest on the hips. Not the shoulders.

- Our advice with packs is same as anything else…start slowly and cheaply, build the empire. It is usually easy to get hold of a second-hand rucksack…most people probably have one already. Use it, see how it feels, and think about the drawbacks. Does it hold enough, does it pinch anywhere? What else should it do that it doesn’t?

- Our advice for an experienced, serious hiker is to have THREE backpacks, to be used situationally:

- A lightweight Camelback or equivalent for light day hikes, biking and trail running

- A larger medium sack (maybe a frameless sack) for more serious day hikes, hut to hut hikes, and maybe a fair-weather overnighter

- A full backpacking pack for multi-day adventuring.

- Train with the pack you are going to be hiking with.

- Remember, it’s not the pack that’s too heavy, it’s what the shaved monkey put into the pack that’s too heavy

One thing to keep in mind is that packs are not generally speaking waterproofed, and this is a pretty big deal since all your gear will be in there. You will need to address this BEFORE you hike. Many people purchase (and some packs come with) a pack cover. Most veteran hikers eventually move away from a pack cover and simply store the gear itself in water proof stuff sacks, or even use a trash bag to line the inside of their pack. That way, it doesn’t matter if the pack itself gets wet because the stuff inside stays dry. Which means you don’t have to worry about slipping on the pack cover every time it rains. We can also tell you from experience that pack overs often fail, or blow off in the wind. But in the early days of your hiking empire, it is perfectly okay to use one.